Unusual Way Of Counting: The Pre-Historic Filipino Way

Did pre-colonial Filipinos count like we do today? Dive into the pre-historic Filipino way of counting, explore ancient methods, and relive history!

Have you ever wondered how Filipinos counted numbers before the Spanish arrived? No computers, no paper nor pencil... just pure, ancient principle!

Have you ever watched a period K-drama like Legend of the Blue Sea, where characters live in two timelines: the past and the present? Today, we are time-traveling, too! 🚣🏿♀️But instead of Joseon-era Korea, we are heading back to pre-colonial Philippines to discover how our ancestors counted their gold, coconuts, and debts! 😁

If you are ready put on our dress code. 🌿 Let us imagine we are in a pre-Hispanic balangáy (tribe). Wear your tapis (wrap-around skirt) if you are a female, bahág if you are a male, plus a putong (headpiece). 🏹 Ready? Let’s dive into this fascinating, forgotten way of counting!

Take a look at the table below:

| Sets Of Tens | English | Tagalog | Mga Bilang (Numbers) |

Sampuan (Tens) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, 2, ..10 | First ten | Unang isáng puô | Isá, dalawá, ..siyám | Sampû (10) |

| 11, 12, ..20 | More than ten | Labis sa isáng puô | Labíng isá, labíndalawá, ..labínsiyám | Dalawampû (20) |

| 21, 22, ..30 | Third ten | Ikatatlóng isáng puô | Maikatlóng isá, maikatlóng dalawá, ..maikatlóng siyám | Tatlumpû (30) |

| 31, 32, ..40 | 4th ten | Ikaapat na isáng puô | Maikaapat na isá, maikaapat na dalawá, ..maikaapat na siyám | Apatnapû (40) |

| 41, 42, ..50 | 5th ten | Ikalimáng isáng puô | Maikalimáng isá, maikalimáng dalawá, ..maikalimáng siyám | Limampû (50) |

| 51, 52, ..60 | 6th ten | Ikaanim na isáng puô | Maikaanim na isá, maikaanim na dalawá, ..maikaanim na siyám | Animnapû (60) |

| 61, 62, ..70 | 7th ten | Ikapitóng isáng puô | Maikapitóng isá, maikaapitóng dalawá, ..maikapitóng siyám | Pitumpû (70) |

| 71, 72, ..80 | 8th ten | Ikawalóng isáng puô | Maikawalóng isá, maikawalóng dalawá, ..maikawalóng siyám | Walumpû (80) |

| 81, 82, ..90 | 9th ten | Ikasiyám na isáng puô | Maikasiyám na isá, maikasiyám na dalawá, ..maikasiyám na siyám | Siyámnapû (90) |

| 91, 92, ..100 | 1st 100 including the sets of tens above |

Unang isáng daán kasama ang mga nasa itaás |

Maikaraáng isá, maikaraáng dalawá, ..maikaraáng siyám | Isáng daán (100) |

They did utilize the base ten (digits from 0 to 9) system. It is interesting to see that in today's Philippine vernacular in counting, locals did not forget the numbers from 1 (isá) to 20 (dalawampû). In contrast, it is apparent that many Filipinos nowadays say the numbers in English rather than in Tagalog if the number is above 20.

Delimitation

This post does not teach you Basic Tagalog Grammar. The following subject matters are not part of this post because they have to be written later:

- Linker 'na' and suffix 'ng';

- 'Labis ng' versus 'labing'/'labím'/'labín'; and

- 'Una' vesus 'ikaisá'.

Completed 10 Versus Uncompleted 10 In Filipino Counting

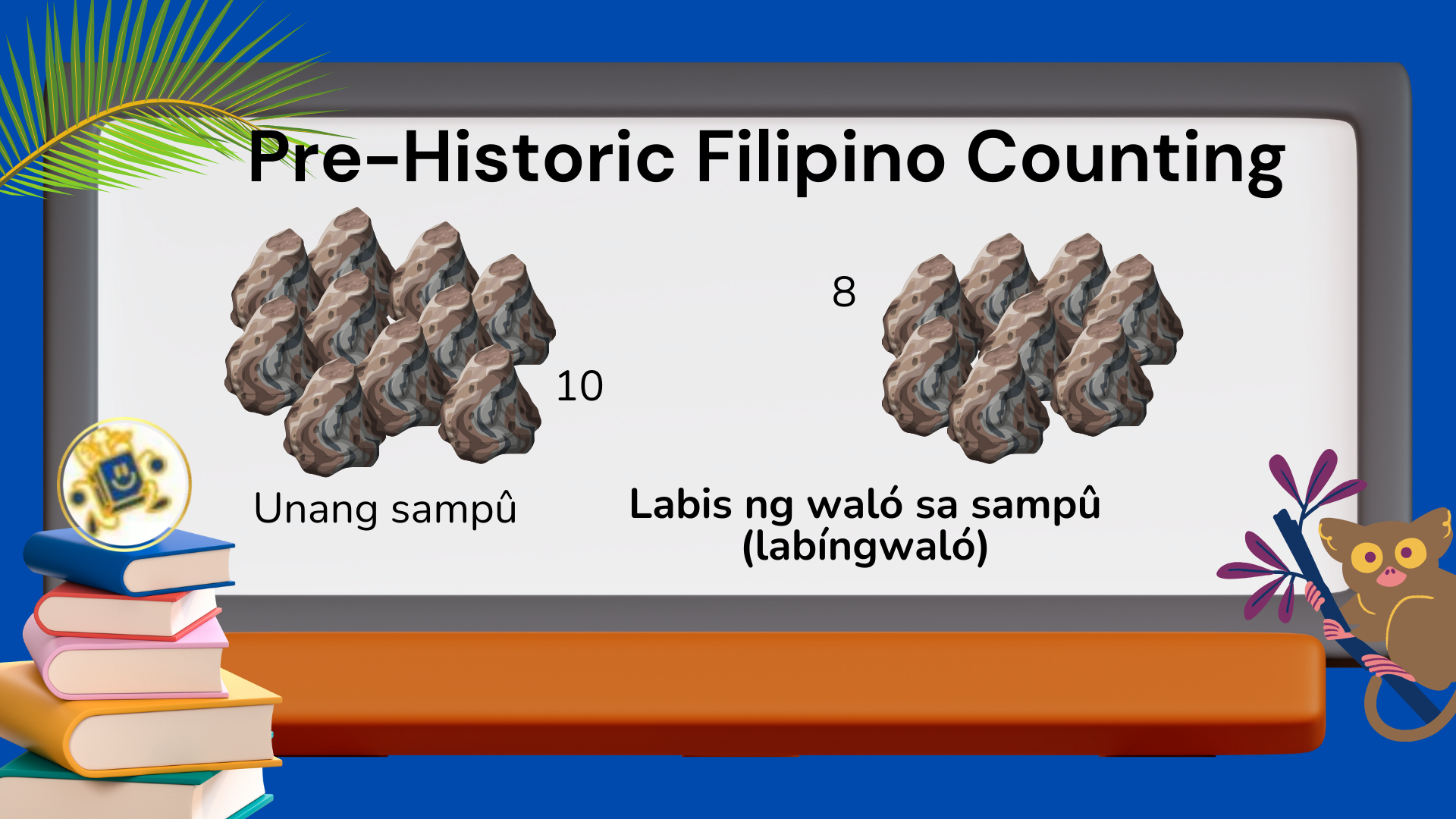

Imagine our ancestors counting things indefinitely. Their tools could either be sticks or stones or seashells, yet they have practiced laying things down in groups of ten.

The first ten, if completed, was called isáng puô while the second ten, if completed, is known as dalawáng puô... and so on and so forth up to siyám na puô (completed 9th ten). Refer to the 5th column on the table above.

Suppose you have 10 stones in the first group but only have 8 stones in the second group. In Tagalog, the total would be:

Labis ng walô sa sampû

The phrase 'labis ng' is shortened into labíng, or labín, or labím, and then used as a prefix as presented in this example: labingwaló (18). Sometimes you would hear folks say: "kulang ng dalawá sa sampû" (2 entries more to complete the 10).

The second group is uncompleted and it only contains walóng (8) entries or elements. These 8 elements belong to the uncompleted 2nd group of 10.

A couple of researchers found out that our Filipino pre-colonial ancestors used the prefix maika or mayka when the number belongs to any uncompleted 10 beyond 20. See column 4 of the table above.

Tagalog Prefix Maika Or Mayka Followed By A Number

I have at least 4 resources to refer to before writing this article and these are listed at the last part of this presentation. Prefix maika or mayka sparked my curiosity and in the end it all make sense to me.

Now let us proceed to my demonstration and here, it gets even more interesting. Bring down 3 groups of stones, or any objects of your choice like shells. Let us say your first 2 groups (tumpók) of objects are both completed tens, but the third one is uncompleted, having only 4 elements. I can imagine our pre-colonial lolo (grandfather) or lola (grandmother) would tell you that you have:

Maykatatlóng apat (24)

Which means: there are 4 elements within the uncompleted 3rd tumpók of stuff, plus the 2 completed tens (implied). See the image below:

Another example: There were 7 tumpôk of shrimps (hipon) on the table but the 7th uncompleted ten only had 2 shrimps. The total hipon your lolo caught was:

Maykapitóng dalawáng (62) mga hipon

This means "there were 2 shrimps in the 7th tumpok" and it's equal to 62; which also means 8 more shrimps to have to complete the 7th ten shrimps. Refer to the image below:

It seems to me, in a philosophical sense, 🧐 that they were seeing the completeness of a whole before its true completion. Their way of counting was not backward per se, but their sets of principles were just different. The way they see things were different, and I think it's worth investigating!

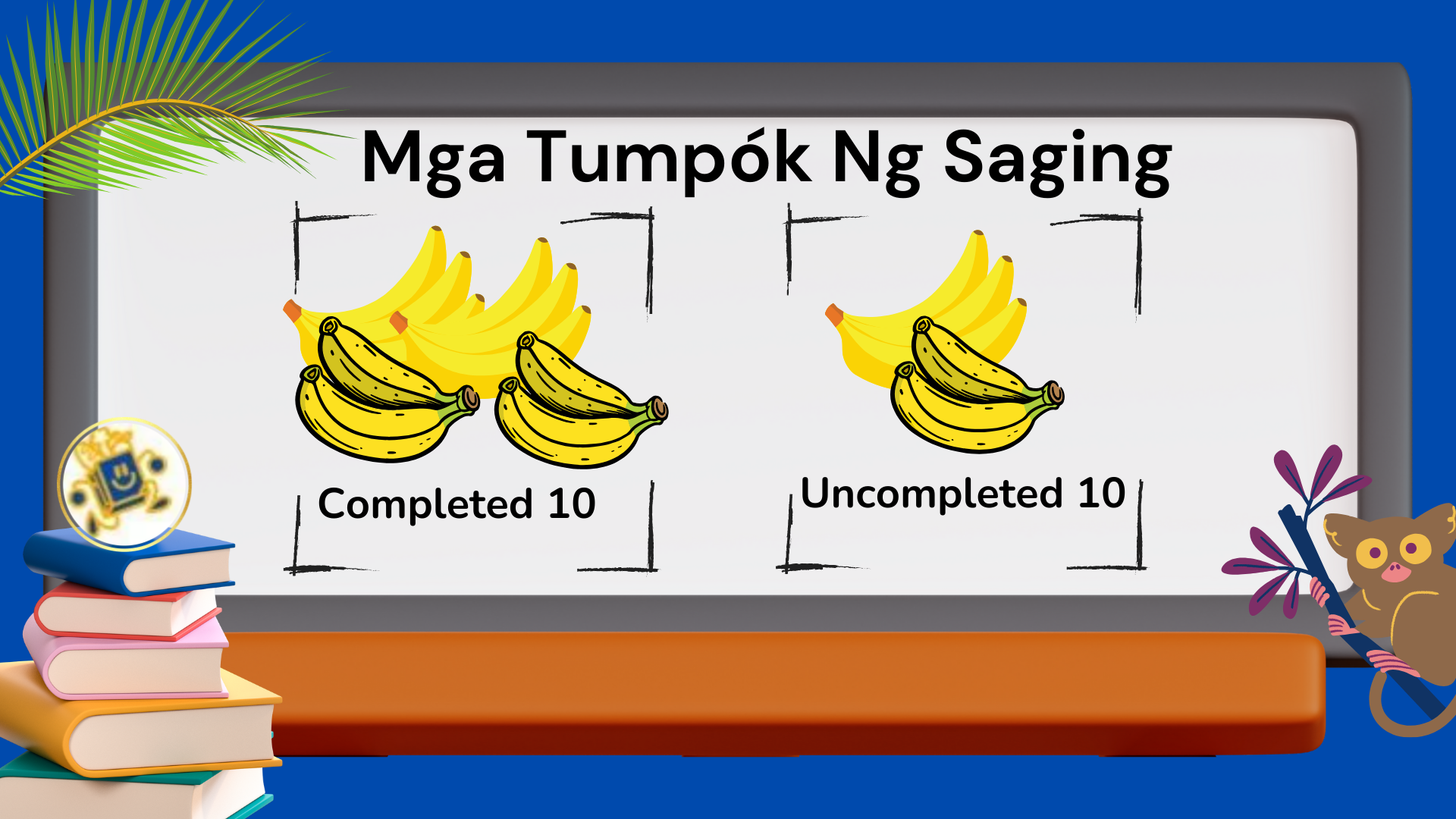

If for example their first tumpók only contains 5 bananas (saging), these bananas are a part of the whole sampû. Even if 5 more are needed to complete the tumpók, they did not focus on the missing parts but rather they put more attention on the completion of the current uncompleted ten. This, I think is the meaning of the prefix maika or mayka.

Figure below demonstrates the distinction between completed 10 and uncompleted 10:

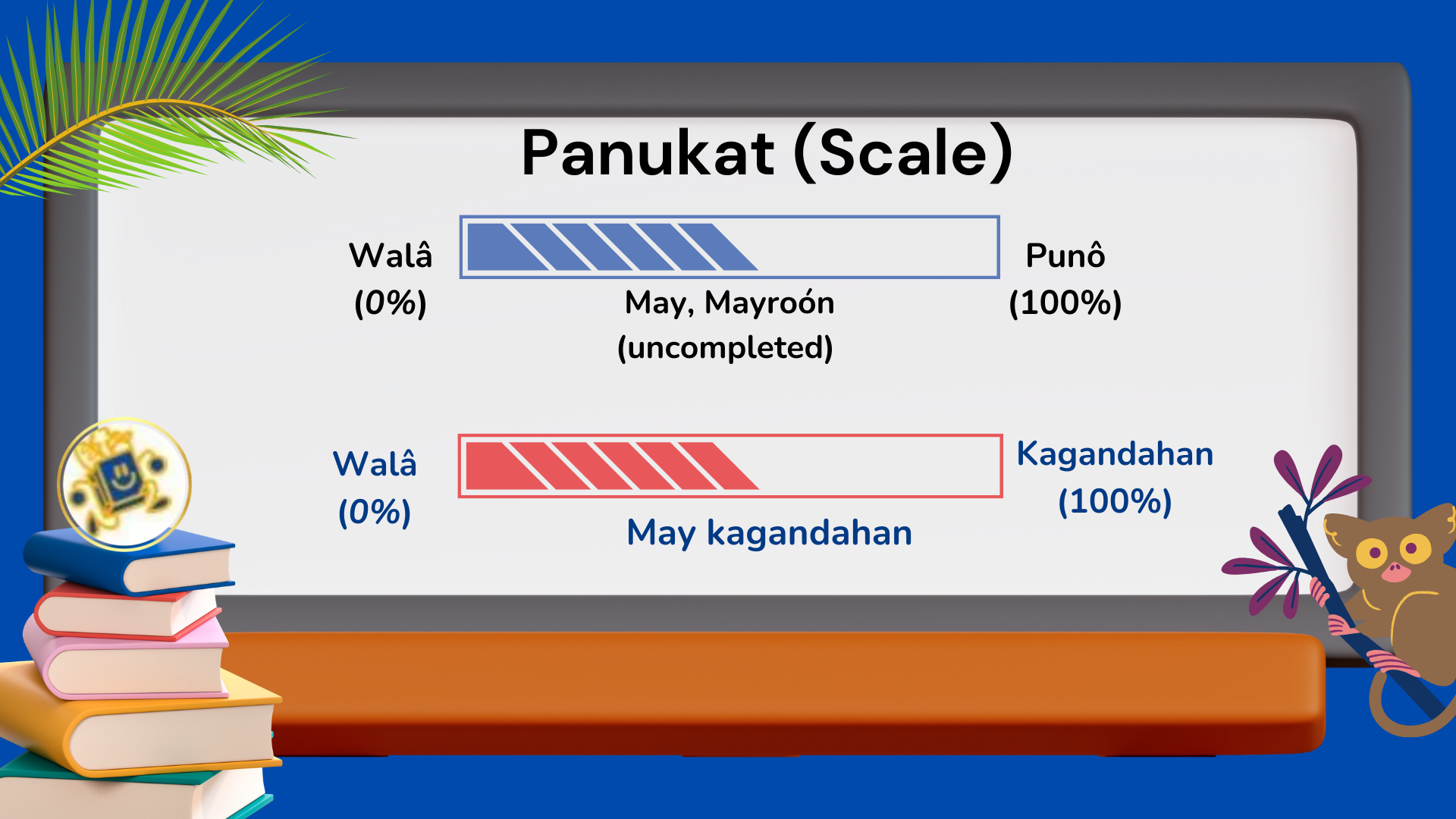

Tagalog Phrases: May Followed By Ka- -an Word

In this section, let us return to today's Philippine vernacular, specifically the phrase with the word may. It has the following phrase pattern:

Where:

"may" is the word synonymous to mayroón which means "there exists", "there is/are", or "have";

[ka- -an word] comprises the prefix ka, followed by a root word, followed by suffix an, which after such conjugation ends up to mean an expression of qualitative concept which could either be an adjective or a noun, or both. The following are examples of such ka- -an words:

- kámahalan (cost or price as an attribute)

- kágandahan (beauty as an attribute)

- káliitan (small size as an attribute)

- kábastusán (rude or disrespectful as an attribute)

- kátalinuhan (knowledge as an attribute)

Putting the word may together with any of the examples above, you will come up with the phrases like:

- may kámahalan (a little bit expensive)

- may kágandahan (a little bit beautiful)

- may káliitan (a little bit small)

- may kábastusán (a little bit rude)

- may kátalinuhan (someone who possesses knowledge but not 100% intelligent)

Example Sentences

- May kámahalan ang niregalo kong singsíng sa kanyá. (The ring I gifted him/her is a little bit expensive)

- May kágandahan iyóng babaeng nasa likód pero mas magandá iyóng katabí niyá. (The girl at the back is a little bit beautiful but the girl beside her is more beautiful)

- Hindî natanggáp sa trabaho ang pinsán ko kasí walâ pa siyáng karanasán at sakâ may káliitan din siyá. (My cousin was not given the job because she/he is inexperienced and besides that, he/she is a little bit small)

- Hindî ka dapat umutót sa haráp ko! May kábastusán ka rin, ano? (You should have not farted infront of me. You are a little bit rude, aren't you?)

- Hindî pò akó matalino, may kátalinuhan lang pò. (I'm not intelligent, I only have some knowledge)

The Indirect Speech Practiced By Many Filipinos

Part of Filipino culture is being indirect. They can play around with words to put themselves on the safe side. They tend to avoid confrontations.

You know that adjectives come in opposites, for example:

- mahál : mura (expensive : cheap)

- magandá : pangit (beautiful : ugly)

- maliít : malakí (small : big)

- bastós : magalang (impolite : polite)

- matalino : mangmáng (intelligent : ignorant)

The may phrase comes handy when:

- You say "may kámahalan ang singsíng" if you want to boost your ego, or "mahál ang singsíng" if you can not afford to buy it;

- You say "may kágandahan ka namán" if you mean "you're a little bit beautiful" instead of saying "pangit ka";

- You say "may káliitan ang bahay namin" if you don't want to leave them an impression that you are bragging;

- And other more similar notions.

With the examples above, do you see the parallel idea or function of these use cases around may ka- -an phrase against the prefix mayka when applied to number words in the previous section? See the image below:

Lope K. Santos, by the way, suggested to use a hyphen between the words may and ka- -an because they are treated as prefixes (a.k.a. clustered prefixes), so they can be written as: may-kamahalan, may-kagandahan, may-kaliitan, and what not.

My personal observation, as a reader of today's literatures including newspapers written in Tagalog, is that: no one uses the hyphen in between may and ka- -an word. I believe we don't have to because may is not a particle.

May is a word. It has meaning and it's just a short form of mayroón, or 'meron' in colloquial speech. I would consider the [may ka- -an] structure as a phrase.

Now that we have a better understanding of may when it is a part of a phrase, I like the idea that may is a prefix if we are referring to the pre-colonial era of counting. In that regard, may is a prefix joined with another prefix which is ka. Therefore, mayka to me is a clustered prefix.

| Pre-Spanish | Current Period | English | May as a | Describes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maykáapat na tatló | Tatlumpú't tatló | 33 | Prefix | Quantity |

| Maykálimáng limá | Apatnapú't limá | 45 | Prefix | Quantity |

| Maykáraáng isá | Siyámnanapú't isá | 91 | Prefix | Quantity |

| ? | May kálaliman | a little bit deep | Phrase | Quality |

| ? | May káhirapan | a little bit difficult | Phrase | Quality |

But wait... 👋 How about maika? Is it different from mayka, or are they the same?

Ordinal Numbers In Tagalog

It seems to me that prefix iká in today's Tagalog grammar will also help answer the question: Why on some occasions maika was used instead of mayka?

Iká is used to express ordinal numbers. An ordinal number is a word or a phrase that indicates the position, rank, or order of occurrence among things or series of events.

Iká is a prefix. In telling time, for example, we say:

- ikasampû ng umaga (9 AM)

- ikalabíndalawá ng tanghalì (12 PM)

- ikaisá ng hapon (1 PM)

- ikapitó ng gabí (7 PM)

Another example of ordinal numbers would be referring to a grade level the child is at in school:

- ikalawáng baitáng (2nd grade)

- ikatlóng baitáng (3rd grade)

Going back in time again, with the concept of "tumpók" or as referred to here as completed and uncompleted tens, it is implied that a particular tumpok has an ordinal attribute. Take the following counting manner:

- ikaisáng tumpók; unang tumpók (1st set of things)

- ikalawá tumpók (2nd set of things)

- ikatatlóng tumpók (3rd set of things)

- at kung anó pa mang bilang (and whatever number follows)

However, part of the elephant in the room is the use of prefix maika. As I reverse engineer this old way of counting, prefix ma comes into the picture.

Prefix Ma In Tagalog Language Indicates Possibility To Happen Or The Action Is Either Intentional Or Unintentional

Let's take a look at a verb group such that it means the action could either be intentional, unintentional or there's a possibility to happen. The ma prefix provides that kind of meaning. See the following infinitive verb examples:

Magawâ (possibility to make or do something)

Makain (possibility to have something to eat)

Maratíng (intention to achieve or to land on)

Matuto (intention to learn)

Example Sentences:

- Walâ kang magawâ sa buhay mo kundî asarín akó! (It is not possible for you to do anything else but to annoy me)

- Maglulutò akó ng tsamporado para may makain ka pag darating ka rito. (I will cook tsamporado so that there is a possibility for you to eat something when you arrive here)

- Tatapusin ko ang kursong Medisina at nang may maratíng akóng tagumpáy. (I will finish the Medical course so that I have the possibility to achieve success)

- Basahin mo ang mga Newsletter ni Albine kung gustó mong matuto ng Tagalog. (Read Albine's Newsletters if you want to have the possibility to learn Tagalog)

With that being said, we arrive at another clustered prefix and this time it is the combination of prefixes ma and iká, provided that the word (or root word) that comes with it is any of the Tagalog digits. See the following:

- Maikatatlóng isá means the possibility to be part of the 3rd ten, or possibility to be part of the tatlumpû; in symbol it is 21.

- Maikatatlóng siyám means the possibility to be part of the 3rd ten, or possibilty to be part of the tatlumpû; in symbol it is 29.

- Maikapitóng limá means the possibility to be part of the 7th ten, or possibilty to be part of the pitumpû; in symbol it is 65.

- Maikasiyám na dalawá means the possibility to be part of the 9th ten, or possibilty to be part of the siyámnapû; in symbol it is 82.

- Maikasiyám na tatló means the possibility to be part of the 9th ten, or possibilty to be part of the siyámnapû; in symbol it is 83.

Am I the only one who thinks that this is an amazing principle? It seems to me that they were more goal oriented in ancient times but willing to proceed from where they are. It seems like they always had the intention to achieve future completion in everything that they do. Will all today's Pinoys reflect on that?

A Contemplation On Filipino Language

This post is one of a kind. It has provided me a great deal of contemplation about Filipino language, and because the subject matter is historical while many words had evolved overtime, I personally believe that it does not matter any more which prefix was grammatically correct: whether it is mayka or maika.

Furthermore, it now makes sense to me why today's natives have difficulty choosing the standard language in expressing numbers. It was generation after generation of adapting western principles of communication and mathematical expressions that leads to near extinction of our native languages, including Tagalog.

Conclusion

As I have presented, pre-colonial Filipinos had a fascinating and unique way of counting; one that was deeply tied to their worldview, language, and daily life. Whether it was distinguishing between a completed or uncompleted ten, using the prefix maika/mayka to express quantity and quality, relying on indirect speech and contextual phrases, or acknowledging any possibilities, our ancestors had a system that was both practical and rich in meaning.

Even today, remnants of these old counting methods still influence the way Filipinos express their thoughts in Tagalog. While locals love using foreign numerals, understanding this ancient system connects us to our roots and gives us a glimpse of how our ancestors thought, traded, and communicated.

So, what do you think? Could you imagine yourself counting the pre-historic Filipino way? 🤔 Let’s keep the conversation going. Share your thoughts in the comment section or reply to my email!

If you have not done already, be a member of this website and I will love to see you grow in your Tagalog journey.

Hanggáng sa mulî, (until next time)

Albine

References

- Paul Morrow; Counting The Old Way: accessed online via Pilipino Express

- Jean-Paul G. Potet; Numerical Expressions In Tagalog: accessed online via Persée

- J. Cordial; Complexity of Old Tagalog Counting System; accessed online via Medium

- Lope K. Santos; Balarila ng Wikang Pambansa

Comments ()